Teachers of calligraphy say that regularly looking at different works of calligraphy is half of practicing the art. This is an advise that I’ve have heard over and over again from many renowned artists and calligraphers including my teachers. It serves many beneficial purposes, such as familiarizing yourself with letter forms and arrangements, understanding composition and script styles and, most importantly for me, drawing inspiration from the work.

Ayman Hassan

One such calligrapher whose work I find highly inspiring is that of master calligrapher Ayman Hassan. His work evokes classical elegance and aesthetics of old masters, but with a breadth of newness.

Ayman Hassan is a Syrian born calligrapher based in Kuwait. He studied with masters in the Middle East and Turkey, including Hasan Celebi, Davut Bektas and Ali Alparslan. He has won many international awards for his work. He also teaches and exhibits all over the world.

I recently reached out to Hassan for an interview, which he very graciously accepted. We talked about his journey to calligraphy, the importance of tradition in calligraphy and his advice for students of the art.

Who did you study with?

I studied with many calligraphers, but initially I didn’t start the traditional way. I first started with Waleed Al- Farood and then I studied a little bit with Syrian calligrapher, Adnan Sheik. But, it wasn’t the traditional way. It was every now and then and they mainly they would advise me on my work.

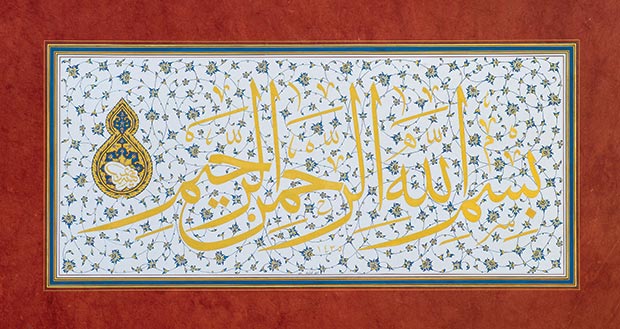

But then in 1998 I met Hasan Celebi. It was an interesting story related to how I first met him. The year before that there was an exhibition in Kuwait and one of his students, Ayten Tiryaki was there. It was the first time I have attended a calligraphy exhibition. Before that I only saw calligraphy in books or prints, and usually it was black and white. So it was the first time I saw calligraphy and tezhip in person, and I was dazzled with that experience.

When I saw Tiryaki’s work, it mentioned in her biography that she studied with Hasan Celebi. I said to myself, if she is writing like this, how well must her teacher write . So, I was really looking forward to meeting him. And, the following year Hasan Celebi attended the same exhibition and that was my beginning with him. Ever since, I have been his student.

How often do you travel to Istanbul?

Well in the beginning it started very slow. I used to send him my work via mail. It used to take one week from Kuwait to Turkey and then a 2-3 weeks until he found time to correct the mesk, and then another one week to send it back in mail. So it was two months between one lesson to the next. And in this way, it took me two years to finish the first lesson, which was “Rabbi Yassir.” And, then I decided this will not work well this way.

In 2000, I just packed my bags and went to Turkey for one week. My teacher would give me one lesson per day, which was unique. Because in the traditional way, you get one class/week. But he gave me a lesson every day and it was more condensed instruction from him. And from that point on, I would see him exhibitions in Kuwait or on my visit to Turkey. In 2006, I spent 6 months again in Turkey, but that was after I received my icazet (diploma).

How important is to keeping this tradition way of teaching?

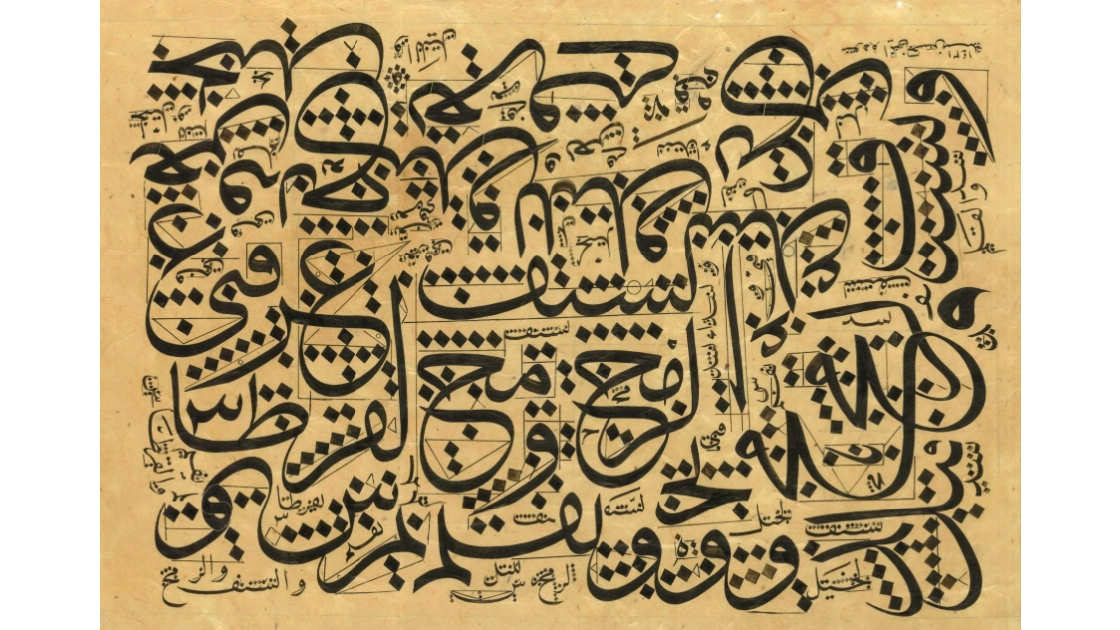

It is important, because it works. But, if we could find a faster and better way to teach calligraphy then it is fine as well. So far no body presented anything that is practical. In general, teaching calligraphy takes 3 to 7 years depending on the student and other things. For example, it took me 7 years to learn Ta’lik script. And thuluth and naskh took me 4 years. That is because I wasn’t living in Turkey, but if I did maybe it would have taken me 2 years, for example. Still, 2 years is not a short period of time. If you compare it to other arts, say painting for example, they teach you the content much faster than what we can teach in calligraphy. So it is a difficult art.

I mean, in painting and sculpture, you imitate from nature, i.e human body, landscapes, animals. But in calligraphy there is nothing to imitate from nature. It is a white sheet of paper and you have to go through it [and produce work] without any guidance. And that’s why it takes a lot of time to learn calligraphy.

How important are rules in calligraphy and do they limit creativity?

There is no limit in calligraphy. Rules in calligraphy are the starting point. Once you master them you can break them, but you cannot break something you cannot see or touch. If you look at the rules of calligraphy, each letter has its own dimensions or proportions, let’s say, “nun” for example is 5 points. But, if you go through the compositions of masters, like Halim, Nazif, Fahmi Efendi, you will notice that sometimes they shorten or enlarge the size of certain letters. So it’s not that rigid like mathematics. The rules are there to maintain the proportion of the letters but the proportions can be flexible when needed. I don’t think the rules limit creativity.

The repertoire of calligraphy can be done in many shapes. The most common is the circular and many calligraphers do that shape because it is challenging. For me, I only did one circular piece.

What makes a piece a great work of calligraphy?

There are two things. And, I will tell you three stories that will demonstrates what makes a good calligraphy.

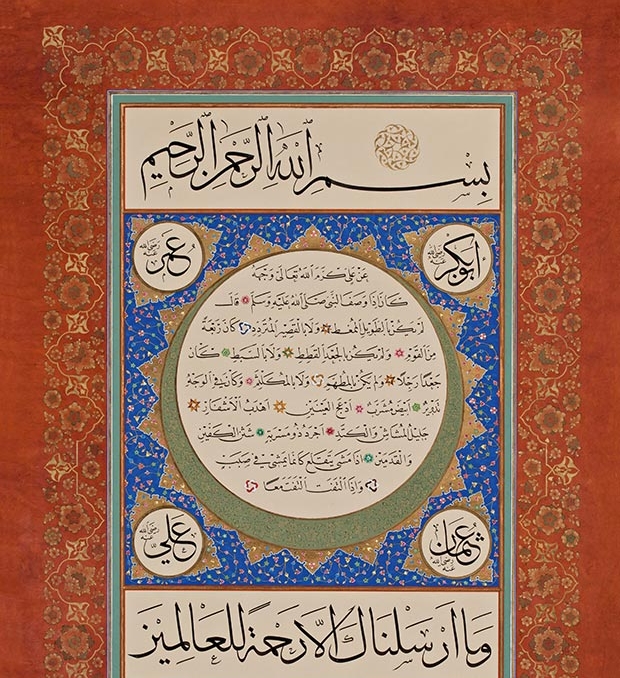

1. During one of my visits to Turkey, I went to see Mohamamed Ozcay. He was showing us a piece of calligraphy that was a hilya [description of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him)]. Initially he had the piece covered and then he gathered all of us in that room and when he uncovered it, we all simply said, “wow.” This effect is the first thing I look for in a calligraphy, which is the “wow” factor.

2. In an another incident, I was once attending a class by Davut hoca at Sulemaniye library [in Turkey] and after the class I had to rush to catch a Turkish language class in Taksim. I was running late. And as I was coming out of the library, I saw this piece written by Sami Efendi and I ended up staring at that piece for 10 mins. I just couldn’t move. This is second thing, [the effect] a good calligraphy or art should have on you.

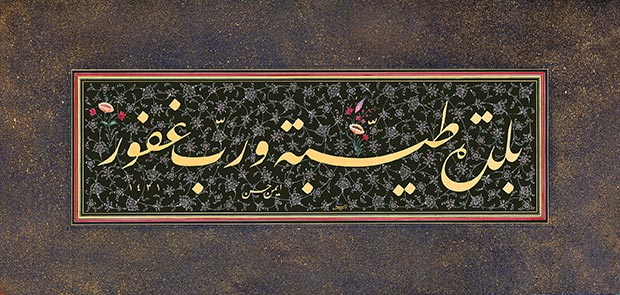

3. Again another story. We were preparing for one of the competitions. I was looking at thuluth kita by Davut Bektas and for the first glance it was beautiful and longer I looked at it the more beauty I uncovered in that piece. And, I found new things that I didn’t see before [in the same piece of art].

At first glance [the best works of calligraphy] should give you a “wow” factor and then should continue to reveal more beauty.

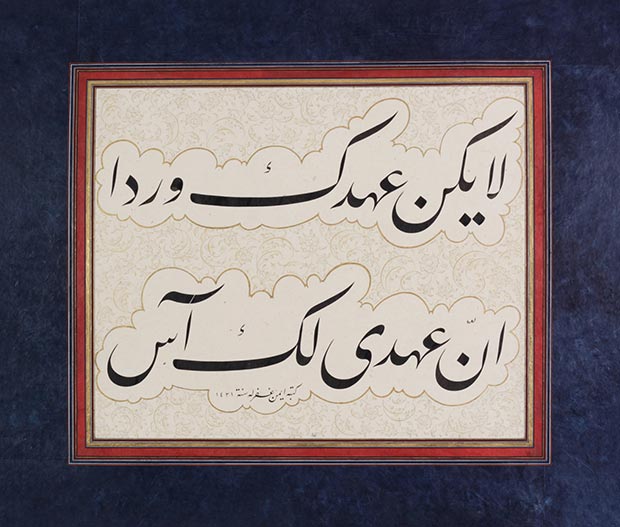

image courtesy of artist

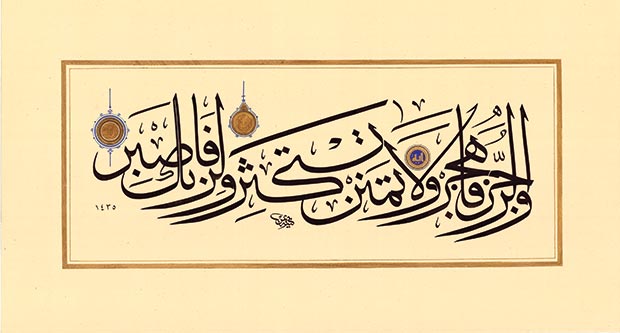

One of my compositions, I did a mirror image or muthanna piece (image above). Once I was in Jumuah prayer and this ayah [verse from the Quran] came into my mind. It was fully composed in my imagination. Once I went back home, I just sketched it and only a few changes needed to be done in the final piece.

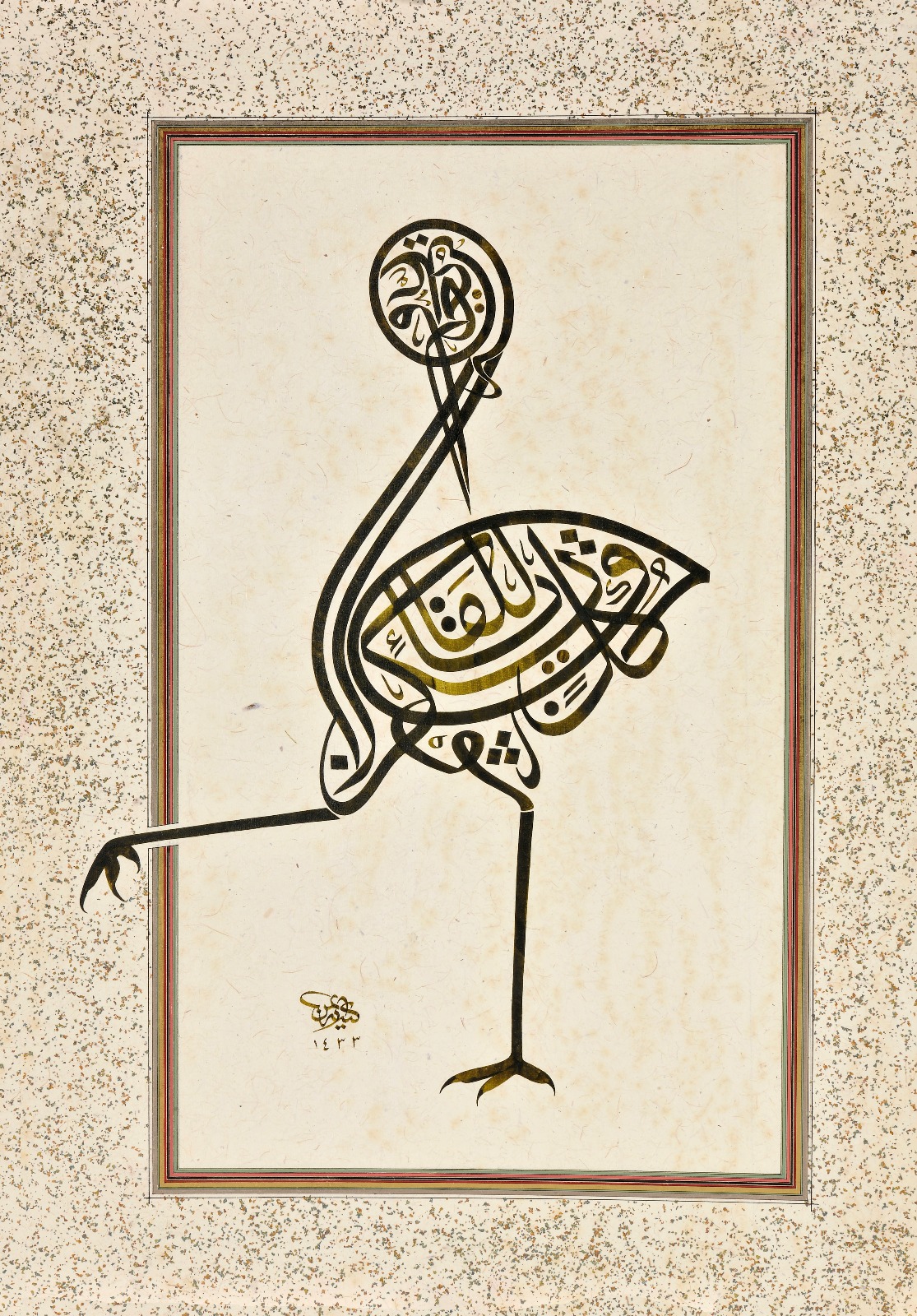

image courtesy of artist

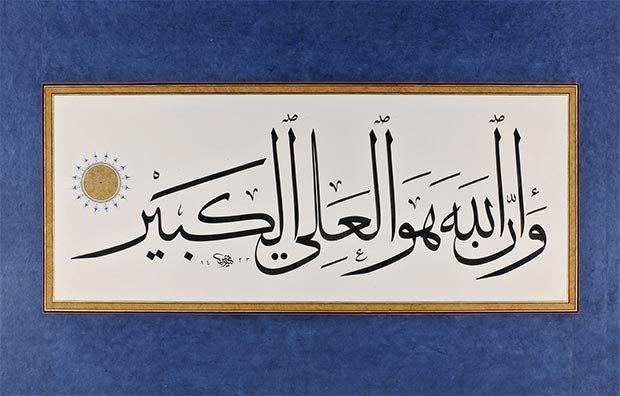

I was discussing a piece with my friend and fellow calligrapher Jassim Meraj, a piece by Mustafa Rakim. He wrote a basmala in a bird form. We were discussing his piece. I had a specific text in mind that I wanted to write, a phrase by Ibn-Arabi. I took a pencil and starting sketching in a bird shape and the draft was ready in 5 mins. It came to me as an inspiration.

I once asked my teacher, Davut Bektas about what is the best way to come up with compositions? He replied, “…the best compositions are those that I have seen with my eyes and they become full. It is not something that I have developed. It is like the text is there and all of sudden I see it fully composed in front of my eyes.” I don’t claim that this is something that I do myself, but I feel in general most calligraphers have the same experience when composing pieces. Other times you have to spend time trying different compositions to come up with a final piece.

I start from the text itself. Many calligraphers start with letters and combinations of letters. I try to have a meaningful text, Quran, hadith and phrases. And, make the compositions from there.

Most important thing you learned from your teacher.

It is a difficult question because I learned many things from my teachers. I have studied with many teachers in Turkey and learned something from each teacher. And among my teachers Hasan Celebi has a very unique way of treating his students. He taught me adab (etiquette) which comes before everything else. Because we are trying to make beautiful things and if we ourselves are not internally beautiful the outcome is meaningless. I feel it is hypocrisy if you are making beautiful calligraphy and dealing with people in a negative way. So this is the major lesson I learned from my teachers in general but particularly from Hasan Celebi. Calligraphy teachers should embody good adab (etiquette). The teachers in calligraphy are role models and play a great role in influencing good character in their students. Otherwise, we will get only beautiful letters without any meaning or depth in calligraphy.

Advice for students of calligraphy

Patience and it (calligraphy) takes time. You cannot learn everything immediately. I would urge all students to learn the biography of Necmeddin Okyay. He was an amazing person. He was a hafiz (memorized Quran), imam, calligrapher, ebru artist, master bookbinder, botanist (had 400 species of roses in his garden), master archer, musician. They used to call him hazerfen (the man who knew a thousand arts) not only he knew these arts but he was a master in all of them. One day I asked my teacher Hasan Celebi about how can Okyay master all these arts. He said that Okyay lived about 92 years and he wasted no time. And so when he used to get tired of practicing one art he would work on another art. So for example if he got tired of doing calligraphy he would go to his garden and tend to his roses and if he got tired of gardening he would go inside and recite a little bit of Quran and so on and so forth. He didn’t waste any moments of his time. He was constantly learning and practicing many different arts. And this required patience and time. But it is achievable as we can learn from Necmeddin.

For more information on Ayman Hassan’s work, please visit his Instagram page: https://www.instagram.com/aymanhassans/